Getting lost in a picture book

For director Lotte de Beer, <i>The Magic Flute</i> has a lot to do with growing up. In her production, animated videos will open the audience’s path into the fantasy world of a young person. On this occasion, dramaturg Peter te Nuyl spoke with stage designer Christof Hetzer and video designer Roman Hansi.

The premiere of the new production will take place on September 14, 2025!

Peter te Nuyl: In the new Magic Flute production, the audience immerses itself in the imagination of a young person. How did the idea of using video as an element come about?

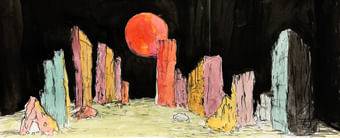

Christof Hetzer: The basic idea was to use painting. A young boy who paints—and the audience dives into this painted world. Only later did the idea arise to animate this painting, to set it in motion. Already for the production of Aristocats we had been looking for a way to use video to show the creation of an image, in other words, to give a glimpse behind the canvas. To experience how an idea becomes a picture, how an invisible hand begins to paint and a stage setting emerges from it. We are now continuing this idea in The Magic Flute, where we truly immerse ourselves together in this animated, painted world.

PtN: What idea came first? The idea of making the young boy the creator of the story? Or of using video more strongly as a storytelling element?

CH: Both ideas arose at the same time. That’s always how it is with Lotte—we sit together and talk about the piece. And everyone wants to share their ideas—and then we realize that we’re actually thinking in the same direction, both dramaturgically and visually!

PtN: The visual world that emerges belongs to The Magic Flute. It wouldn’t be conceivable for any other work, right?

CH: No, at the beginning there was the figure of this young person who tries to cope with his experiences by putting them on paper, by painting them. From this idea the entire visual world sprang.

PtN: How did you then decide what this visual world would look like, what its aesthetic would be?

Roman Hansi: We experimented with different styles, with different ways of painting. The individual elements should be aesthetically appealing, while at the same time retaining something childlike.

PtN: From what you’ve described, one could also think of an animated film. But what we’re doing is a theater performance. How should we imagine the interaction between stage and video?

CH: We are working toward a performance in which these boundaries dissolve. You open a picture book and dive into that world. There is no distinction between acting, music, stage, or video—it all merges into a single world. That would be the ideal outcome!

RH: We’re approaching this outcome in two different ways. For instance, the costumes will look as if they are painted, and at the same time we are filming the performers for the animations and transferring their movements to the drawn figures.

PtN: Would this have been possible five years ago? Or is it only thanks to new technologies that this visual world can be created?

CH: It would have been possible, but with considerably more effort! Now we can achieve it for a production like ours, whereas in the past you would probably have needed thousands of individual drawings.

RH: Both in creating the visual worlds and in stage technology, there are now new possibilities that allow us to truly interweave projection and stage machinery. In the past few years, we’ve made huge progress in this area.

PtN: That all sounds very technical.

CH: The art lies in making it look not like technology in the end, but like poetry!

RH: And at the same time, technology helps us here as well. New virtual studio options allow us to quickly see how something will look on stage—and whether it achieves the desired effect.

PtN: But you still need live singers on stage, right?!

CH: Absolutely! That’s exactly where the fascination lies! Mozart’s music is highly theatrical—he was almost obsessed with finding and inventing theatrical effects in his music. To connect that now with high-tech, to let the two worlds inspire each other—that’s what excites me.

PtN: And you, Christof, you actually still draw very much by hand, in an analog way.

CH: Exactly, I draw a lot physically. The art is to teach the machine so that in the end it looks as if it were painted by a human hand. And I believe you can very clearly see what was drawn by a human and what was not. That’s the human element—that’s something AI cannot yet achieve.

PtN: If imperfection is the human element—where do you find that in Mozart and Schikaneder?

CH: I assume the question isn’t meant in a strictly musicological sense! Let me answer in a roundabout way: sometimes, even with great composers like Mozart, it’s fascinating to listen to the music that doesn’t belong to the greatest hits. There you can often hear a musical idea in the process of emerging. And if you listen to Gluck after Mozart—you can also experience how a musical idea is born, how it develops, and finally reaches a point where something new has to emerge.

PtN: A question about rehearsals for The Magic Flute. Does the visual storytelling limit things, since so many decisions for the videos have to be made in advance?

CH: The work changes, of course. We demand a lot from the performers. They have to imagine a great deal for a long time, because the videos aren’t there yet. And then, suddenly, at a certain point, a lot is there—when the visual world is added. But the ensemble is still allowed to play very freely; the videos aren’t overly detailed and leave plenty of freedom on stage.

PtN: In the performance, the sketchbook of a fourteen-year-old boy comes to life. Did you draw on your own childhood and youth for that?

RH: Not consciously. But I have two children myself, and I find it fascinating to observe in which phases of growing up you invent which pictorial worlds. My youngest, for instance, is currently painting only in blue—he’s practically in his blue phase! My eldest mainly paints cars. It’s exciting to see how these visual worlds evolve.

CH: What I remember most is what it was like to discover pictorial effects as a young person. When you begin painting, those effects are enormously important. I once noticed, for example, that I was good at drawing hatching, shadows, and folds—so for a while I kept drawing crumpled things. In our work on The Magic Flute, we often thought we needed to make sure it didn’t look too skillful—after all, it’s supposed to be a young boy painting. But why shouldn’t he arrive at some good effects and use them? At that age, you absorb the world like a sponge, trying out different styles—that’s incredibly liberating when creating a visual world.

PtN: Do you often look at your own drawings from earlier times?

CH: Yes, and then I discover that I’m actually still interested in the same things, that deep down I’m still the same person.